|

The Toolbox for Rapid GHG Emission Reductions

by Young-Jin Choi Humanity is on a “race to zero”, a mission of historic significance to reach netzero CO2 emissions before 2050, followed by negative emissions (as well as netzero levels for other greenhouse gas emissions) shortly thereafter. Assuming a carbon budget of 340 Gt CO2 - which corresponds with a 67% probability of staying within 1,5 ° C - net-zero CO2 emissions would even need to be achieved by 2040. Considering that global emissions have not peaked yet but are even projected to continue to increase in the near future, it is apparent that winning the “race to zero” requires a rapid and deep decarbonisation at a much faster pace than is currently the case.

In order to accelerate the speed at which decarbonisation occurs (both domestically as well as internationally) governments can utilize a toolbox comprising a variety of possible climate policies, including (but not limited to): Economic Incentives

The Case for GHG Emissions Pricing

Among these regulatory and enabling interventions, the pricing of GHG emissions represents a critical cornerstone of a comprehensive climate policy package. The basic idea is that prices should be increased for those economic activities that society deems undesirable, especially when markets fail to properly take the costs and damages resulting from these activities into account. The on-going market failure with regard to the pricing of greenhouse gas emissions has been well established. As a result, economic profits and financial returns of fossil fuel-related projects are substantially higher than required to safeguard the well-being of young & future generations. Higher prices for GHG emission-intensive goods and services can correct this market failure in accordance with the “polluter-pays principle”, while improving the relative competitiveness of climate solutions. Market forces are utilized to accelerate the development of new climate solutions and the deployment of existing ones. The strength of the economic incentives and disincentives provided by GHG emissions pricing depends on its scope, its price level and its growth trajectory. The “Network for Greening the Financial System” (NGFS), for example, assumes for its “orderly transition scenario” an average global price level of 100 USD/ton by 2030 increasing to 300 USD/ton by 2050. Concerns about international competitive disadvantages and carbon leakage driven by emissions pricing can be effectively addressed by a well-designed carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM). As more countries/regions establish ambitious GHG emissions pricing schemes in order to avoid border tariffs and generate carbon-pricing revenues for themselves instead, the need for a CBAM declines over time. If designed and implemented well, GHG emission pricing by itself has the potential to substantially accelerate the speed at which decarbonisation occurs. Of course, emission pricing alone is not likely to suffice to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement. Thanks to extraordinary technological improvements, renewable energy generation has become substantially more competitive over the past few years, for instance. But without a correction of the aforementioned market failure, the pace of decarbonisation will likely remain too slow, as the “production gap report” by UNEP illustrates. At this late stage, after having essentially lost 30 years, an “all-at-once” approach is needed, utilizing the full potential of the climate policy toolbox to maximize the chances for successfully stabilizing global temperatures at a sustainable level. The potential benefits are huge: For example, the IMF has recently projected a 13% increase of global GDP by the end of this century relative to “business as usual” for a policy package that combines GHG emissions pricing with a green fiscal stimulus. In addition, there are substantial co-benefits in terms of improved air quality and human health, avoided biodiversity losses and long-term price stability to be expected. Arguments in Favour of Using GHG Emissions Pricing Revenues for a Climate Income

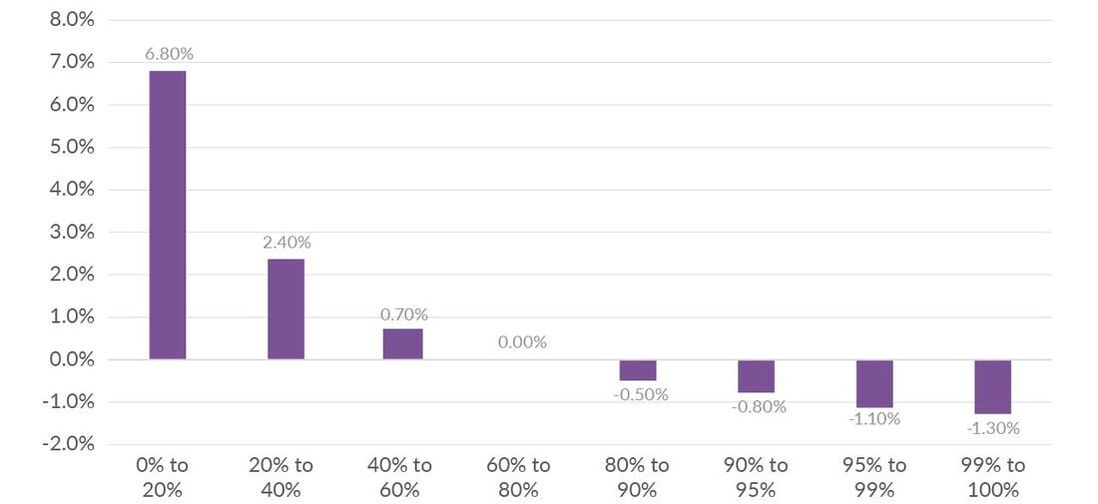

Without sufficient public support, any climate policy is bound to fail. As the well-known example of the Yellow Vest Protests 2018 in France demonstrates, there is a substantial risk of a public backlash. The fact that price increases for fossil fuels and other GHG emissions-intensive goods and services are putting consumer households under increasing economic pressure represents a political challenge that demands to be addressed. How can the public's support for rising GHG emissions prices be ensured and sustained? The answer is simple and provided by the concept of a Climate Income (also known as a “carbon dividend”): All (or most) of the revenues generated by GHG emissions pricing would be equally distributed to consumer households in order to increase their capacity to absorb price increases and enable them to reduce their carbon footprints over time. After all, higher upfront purchase prices and investment requirements often represent a key obstacle to the take-up of low-carbon technologies. Moreover, a Climate Income would create a powerful incentive to adjust consumption patterns and benefit from an even greater share of extra income. Assuming 100% of GHG emissions pricing revenues are distributed, about two thirds of all households - especially low-income households – whose climate footprints tend to be significantly lower in comparison to high-income households – could even gain more than they would “lose” to price increases. The Tax Foundation has simulated the positive distributional effects of a “carbon tax and dividend” scheme starting at 50 USD/ton and increasing by (a rather modest) 5% p.a. in the US: The Distributional Impact of a Carbon Tax and Dividend

Percent Change in After-Tax Income. Source: Tax Foundation General Equilibrium Tax Model, April 2019

The administrative burden for a Climate Income would be relatively small, especially when already existing systems with sufficient reach (e.g. health insurance) can serve as a backbone. The remaining “unbanked” could be reached by state-issued prepaid debit cards or other targeted welfare programs, for example. In addition, the equivalent of monthly checks to all citizens - ideally paid upfront - would make the government's consideration for the needs of its citizens tangible and transparent, thereby enhancing political trust. It would also be difficult for newly elected administrations to reverse the Climate Income legislation. In fact, the implementation of a Climate Income could send a powerful positive message that is largely immune against populist attacks, such as: “No one should be left behind. Together we can rise up against the greatest challenge of our time”. Further supporting this point, a Climate Income would be revenue-neutral - neither would it increase the size of the state nor would it give a reason for public mistrust (whether justified or not) in the effectiveness and consistency of other possible uses for emission-pricing revenues described in the next section.

Other Possible Uses of GHG Emission Pricing Revenues

Besides a Climate Income, other possible uses for emission pricing revenues include:

|